Costa Rica 1992

This is mostly a personal page for Jann and me to help us remember and relive a wonderful visit to Costa Rica over 33 years ago. But you are certainly welcome to read it and view the photos. I thought of creating this recently because of a planned return to Costa Rica in Spring, 2025.

Shortly after returning from our 1992 trip, I wrote a “Trip Report”, initially for the newsletter of the company where I worked. That report is reproduced here in Roman type. The text in italics has been written recently to further describe the trip and the photos.

The photos presented here are not up to modern standards for several reasons. First, I wasn’t a very capable photographer back then, though I tried hard. Second, the photos were shot in early 1990s-era slide film, which among other things, suffered from low dynamic range making photographing in high contrast situations problematic. Third, what you see here are simply photos of the original slides. I “digitized” these slides by taking a picture of them and then doing a bit of post-processing.

This trip was back before I took decent notes, and the metadata on the slides did not help. So perhaps some of the place names are incorrect. But I have worked to make this story mostly true. And the pieces reproduced from my “Trip Report” were reasonably accurate as of 1992. Although it is hard to believe, I know those much younger photos of Jann and me are real.

In late February and early March 1992, Jann and I spent sixteen days in Costa Rica (not counting a day each way to get there and back). We had a great time and very strongly recommend Costa Rica as a vacation destination, except for those who want to dive or tour Mayan ruins. It has endless beaches on both the Pacific and the Caribbean, rain forests, mountain ranges, lush vegetation, excellent weather (at least if you go during the dry season, which we did), surfing, white water, windsurfing, fishing, birds, flowers, wildlife, excellent food, and very friendly people.

Costa Rica has been a democracy since 1889 and has a larger percentage of its land devoted to national parks than any other country in the world. It is a well-developed country with decent roads and water you can drink. Telephone and electricity are nearly everywhere. It has no military. San Jose, its capital, has some big city problems such as traffic and petty theft, possibly exacerbated by refugees from neighboring war-torn countries. In 1987, President Oscar Arias received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in Central America. In May, Arias speaks in Hanover at Dartmouth’s Commencement.

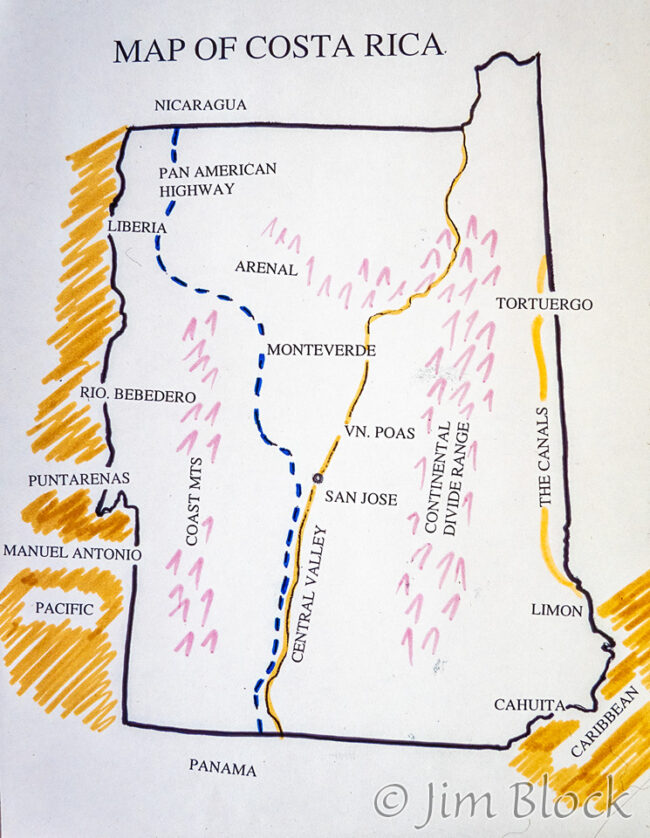

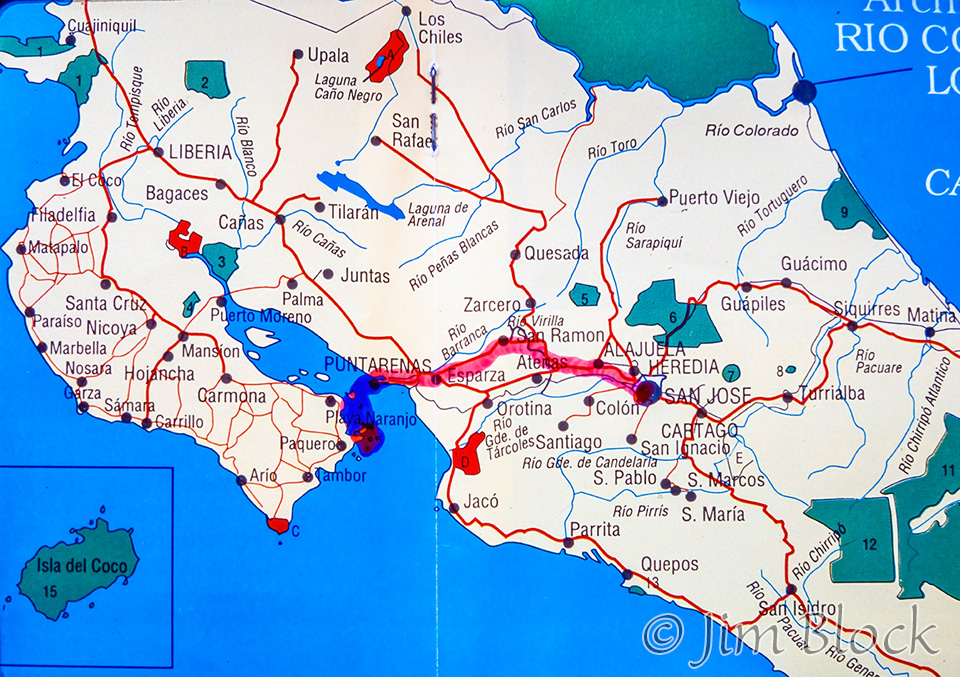

Costa Rica is virtually the same size with twice the population as Vermont and New Hampshire combined. (See map below of Costa Rica overlayed on VT and NH.) San Jose is situated in a broad central valley (“Mesta Central”) surrounded on the east and west by mountain ranges, just as Hanover is bordered by the White and Green Mountains. Beyond the mountain range to the east (which forms the continental divide) is a relatively short Caribbean coast.

The Caribbean coast consists of sandy beaches to the south and low-lying wetlands with an inland canal and fantastic fishing to the north. To the west lies a much longer Pacific coast containing rain forests, rocky cliffs, and beautiful sandy beaches. The northern part of the country is hot and dry and borders Nicaragua. The southern part tends to be rainy and borders Panama. During the rainy season it rains everywhere. Like Hanover, there are many things to see and do within a two-hour drive of San Jose.

We stayed our first week in a beautiful Aparthotel in Escazu, a suburb of San Jose. An Aparthotel is a cross between an apartment and a hotel. Ours consisted of 8 units surrounding a swimming pool and gourmet restaurant with our unit having two bedrooms, a living room, a full kitchen, a laundry room with washing machine, a bathroom, several TVs (80+ channels), and a private parking space, at about $60 per night. After the first week we traveled around the country mostly without reservations.

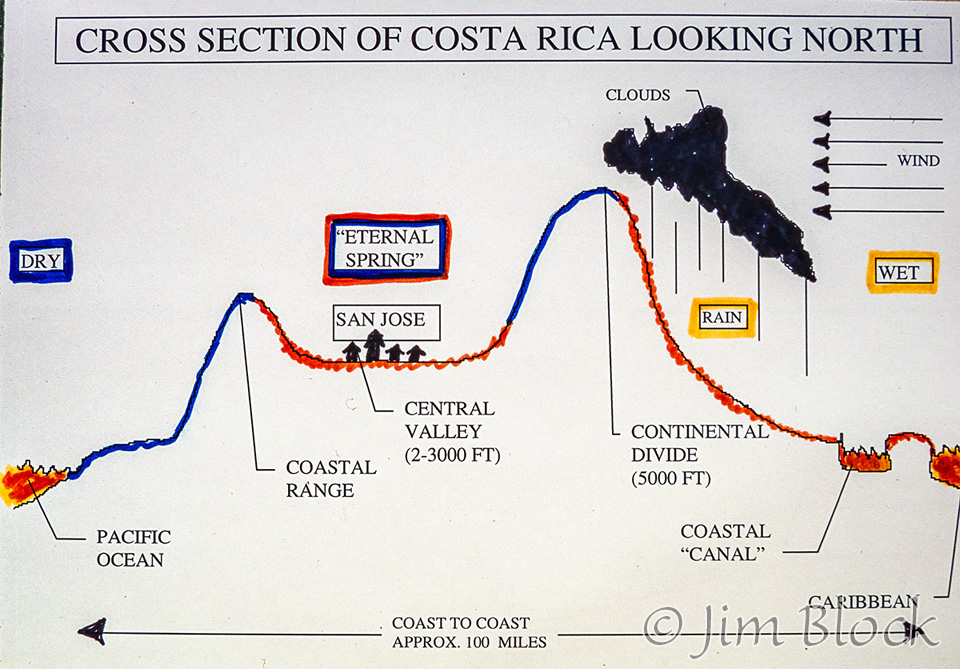

In many ways the climate of Costa Rica is nearly perfect. San Jose is called the City of Eternal Spring. Temperatures in San Jose are 72°F ± 10°F day or night, winter, summer, fall or spring. In fact in San Jose the temperature varies more between day and night than it does between January and August.

Although Costa Rica is north of the Equator (but fully in the tropics), they call December to March “Summer”. This is the dry season and this is when children have their long school vacation. While we were there (early March), we saw children starting school registration with parents; shopping for notebooks, pens, and rulers; and the first day of school. Uniforms (navy blue) were the norm.

On our first full day we passed a barber shop, and I took photos through the window of kids getting haircuts before the start of the school year. This was a sight that will always remain in our memories and in a few photos. One child had to be held still by his mother and sister while a second sat regally still like a man of the world.

Beyond excellent climate, the weather in Costa Rica is, to a large degree, under your control. If you don’t like the weather where you are, drive a very short distance (10 or 20 miles) and it can be very different. (Altitude is the major factor.) Furthermore, you know exactly where to go since the weather patterns change very little from day to day. This is mostly due to the fact that the prevailing winds (from the east) bring moist Caribbean air inland. As the air encounters the mountains and rises, clouds form, and it rains. There are microclimates everywhere, governed by geography. We experienced that dramatically our first day in Costa Rica.

Our first full day was our wedding anniversary and we were off at the crack of dawn. (Sunrise and sunset is basically 6:00 am to 6:00 pm year-round.) We headed north toward the mountains and the Poas Volcano about an hour and a half away. The early morning was perfect, low 70’s and bright sun. About 10 miles from the entrance to the park, we spotted a rainbow. I snapped a few pictures not realizing what the rainbow was telling us until we got about 2 miles from the park entrance. There, it started getting a bit foggy, and a minute later it was raining. We drove to the entrance and sat in the rain for a few minutes trying to decide whether we should wait here the 20 minutes before the park opened (we were early as usual) or drive around a bit.

We opted to drive around a bit. There was really only one direction to head, so down the mountain we came. A few minutes later we were back in the bright sun. After buying some delicious elephant ears (a sweet flaky pastry the size of a pizza) at a roadside stand, we head back towards Poas optimistic that by now the sun had burned off the little bit of cloud we had experienced. Wrong! Although we walked in the rain to the edge of the volcano, we saw absolutely nothing but dense fog and it was cold. We wore rain ponchos but would have really appreciated thick sweaters and windbreakers under the ponchos.

We returned to the car, turned the heater on full blast, and headed downhill. Five minutes later we were in bright sun and a few minutes beyond that we had dried off enough to turn the heater off and buy more elephant ears and fresh strawberries. Fifteen minutes later we stopped in a small town to stretch our legs and were astonished to find the outdoor temperature was over 800F. Throughout the remainder of our trip we moved rather swiftly through areas that were too hot, too cold, and mostly just right. And when it was too hot there was almost always an ocean nearby to provide instant relief.

But we eventually did make it to the Poas Volcano in sunlight that morning. Here are two photos.

Also on our first day we visited Sarchí, Costa Rica’s most famous crafts center. The most popular items on sale are “carretas”, elaborately painted oxcarts that traditionally carried coffee from the highlands down to the port on the Pacific coast. Here are the painters at work.

Traveling Around

Driving around Costa Rica is a pleasure because of the sheer beauty of the scenery. It is a very lush country; beautiful flowers and birds intermingle with fruit plantations and coffee fields. There are many good roads (virtually all of them are two lane) and many terrible, bumpy dirt roads (sort of like NH and VT without interstates). Nowhere in the country is the speed limit above 80 kilometers per hour (about 50 mph). Buses and trucks belch pollution, so driving in a closed car with your air conditioner on is necessary on the main roads or in town.

Drivers are aggressive — I characterize them as somewhere between Boston and Athens drivers, although Jann thinks they are not that bad — and no one slows down for pedestrians or jaywalkers (which are everywhere). It is not uncommon to share the Interamerican Highway with old men riding wobbly bicycles (it’s real scary) and, in the middle of nowhere, a bus will stop (on what is equivalent to our interstate) right in the middle of the road to let passengers on and off. Occasionally you must stop to pay a toll of approximately 10 cents. When you do, you are religiously handed a receipt — in Costa Rica you get a receipt for everything.

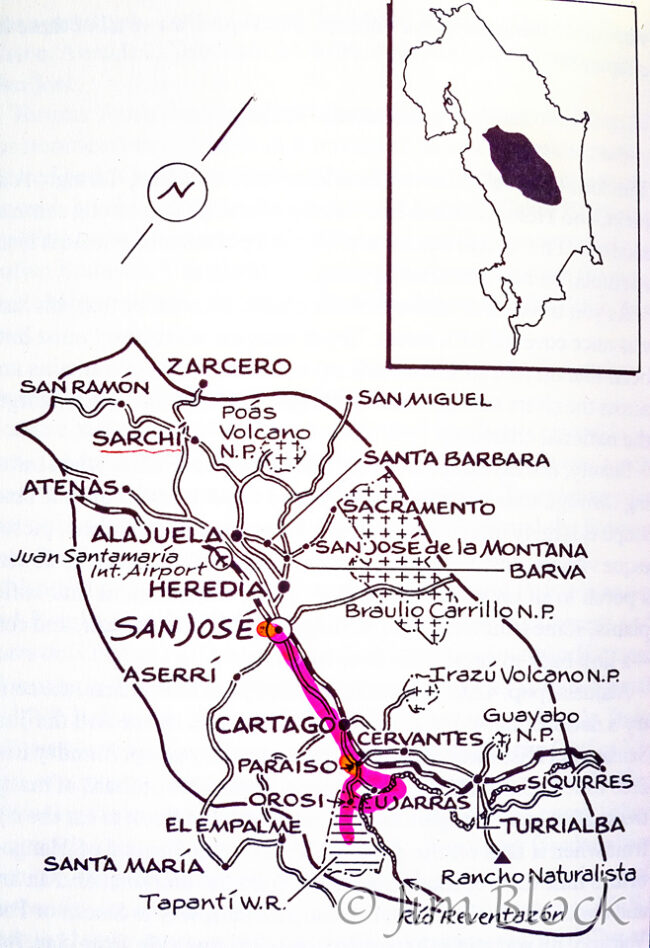

Here is a very rough diagram of the places we visited and the routes we took.

Remember the “Back to the Future” gas station scene where eager attendants rush around washing windows and checking oil, tires, and battery while pumping gas? It’s a bit like that in Costa Rica. No self-service gas: you cannot pump your own. And you do get lots of service. All windows get washed with a large very soapy sponge on the end of a pole. And then they are hosed off with lots of water. It’s a surprise the first few times it happens, but the windows (and much of the car) get clean.

Road signs are erratic at best, but the people are very friendly, so you often stop and ask for directions. It was common to enter a small town and not be able to figure out which of the many options presented led out of town toward our destination. Once, when we were headed toward Santiago (a small mountain town enroute to the Pacific) we entered a town, drove a little bit beyond the central square, realized we didn’t know what we were doing, and asked directions. The people pointed back toward the central square. We drove through it, tried another road for about a quarter mile, and asked directions again. Again, we were directed back toward the center of town. This time we asked a man standing right by the center of town. He looked at us rather strangely when we asked “Santiago?” and then laughed and pointed straight down. I guess we had made more progress than we thought we did.

I was surprised to see how few people in Costa Rica spoke English. So, when you asked for directions, you got a lot of Spanish thrown at you. If you were lucky, the person would also use a lot of hand signals. We found we could do a good job figuring out how to get out of town without knowing any Spanish just by watching the person explain what to do.

Observations on Daily Life

Life in Costa Rica had several interesting characteristics including a passion for official numbers and security. Although Costa Rica has no military, guns (pistols) are commonplace. The night watchman at the hotel carries one. Three or four nice looking young men hanging around the checkout clerks at the grocery store have pistols in holsters. The restaurant valet (a 20-year-old kid who points to the parking space) guards the lot armed with a pistol. Even the ticket takers at the national parks carry one. And if you walk past a bank in a small town you are virtually certain to see a guard leaning on the wall outside the building carrying a mean-looking rifle.

In and around San Jose most people live behind bars. Their yards are well fenced with imposing iron bars and locked gates, and all the windows of their houses have bars. Often the front yard is patrolled by a large dog. Sometimes, in the upper-class areas, there are actually guards and/or video cameras. In middle class neighborhoods (most of Costa Rica is the middle class; we saw no slums although in rural areas some of the houses were exceedingly simple) the attention to security is less impressive but still present – barbed wire everywhere. This characteristic is much diminished in the countryside (away from San Jose), but it is rare to see an expensive house anywhere in the country without a measure of “protection”. I could not determine the extent that all this security was needed versus how much of it was cultural paranoia.

As we explored Escazu near our Aparthotel the first day, I took these photos.

A somewhat different, but perhaps related observation, is that the Costa Ricans are very conscious of identification numbers. I was continually being asked for my passport number and, of course, I never seemed to have my passport in my pocket when I needed it. After innumerable trips to the trunk of the car, I finally realized that no one really cared if they saw my passport or not, they just wanted my number. And then it dawned on me that any number would do, I could make up one if I wished. At one hotel the clerk pointed to a space and said, “put your number there”. I asked which one, and he said, “passport or social security or…” He just sort of trailed off. It didn’t seem to matter much what number I put as long as he had a number for his form.

There are three basic approaches for changing dollars to colons. First, you can simply attempt to pay with American money. This works smoothly about 80% of the time. Second, you can change your American money for Costa Rican at any hotel quickly, easily, and at a good rate. It’s like getting four quarters for a dollar in this country, except you hand them a $100 travelers check and you get 13,800 colons. Third, you can change your money at a bank. To accomplish this, you stand in line for 15-20 minutes, fill out a couple of forms, show your passport, get a few stamps and then proceed to a second line for another 15 minutes. Eventually you pay a service fee and change your money. I never did this though I observed the process firsthand once and read about it in several guidebooks.

A final note on money, everywhere except in grocery stores people dealt in colons as the unit of money. In grocery stores, items were priced in 100ths of a colon (centimos). When they give you change they round off to the nearest 5 centimos, so you get some 5 centimos coins. Given that 100 colons are worth about $0.70, a 0.05 colon coin sure can’t be worth much.

Eating Out

Food in Costa Rica is inexpensive and quite good. Fresh fruit is everywhere, and native beef is a common and delicious menu item. A filet mignon dinner at a gourmet restaurant with salad and dessert would typically cost less than 1000 colons (around $7). At one small restaurant where we stopped for lunch, a typical Costa Rican meal (all the rice and beans you would ever want to eat at one sitting) cost 300 colons ($2) for the two of us including tax and tip.

I don’t care for the way tipping is handled in Costa Rica. Basically, they add 10% service charge to the meal. The guidebook instructs that tipping is not necessary, but if you feel the service has been truly excellent, you can leave a few percent additional. This custom has two problems. First, if you get lousy service (which was rarely the case) you can’t leave a reduced tip; you’re stuck with the 10%. At the other extreme, when you have excellent service and want to follow what the guidebook recommends, you feel real guilty at the size of the tip. Since a dinner meal for two would cost around 2,000 colons, a few percent is on the order of 50 colons. So, you really splurge with the tip and pull out a 100 colon bill only to realize that you are about to leave a 70 cent tip! It just doesn’t seem right. And since there have been three waiters attending to your every need, they are going to have to split those 70 cents. Even if you increase the tip considerably, you still walk away feeling somewhat guilty.

It is common for a restaurant to have both Spanish and English menus. It is unfortunate that they try to do this with two separate menus rather than a Spanish menu with an English translation underneath. The problem with two separate menus is that quite often there is not always a one-to-one correspondence. Under the fruit drink section or the entree section or whatever, there might be seven items on the English version and nine items on the Spanish (or vice versa). So, when you order, as I did, blackberry juice and point to it on the English menu, the waitress notes that it is the fifth item down and proceeds to bring you the fifth item down on the Spanish menu. At one restaurant I tried numerous times over a two-day period to get a taste of the blackberry juice before I finally gave up believing it was just a figment of the imagination of the person who happened to type up the English version of the menu.

By the way, when you order a fruit drink in Costa Rica they grab the fruit or fruits (fresh of course) and toss them in a blender. During our trip we had the strangest and most wonderful fruit and fruit drinks I have ever experienced in my life. Fruits I have never eaten before were common and delicious. And there was usually someone around to teach you how to eat them (which was not always obvious).

Tiquicia

Our first meal in Costa Rica — not counting the elephant ears we munched on all that day — was a real experience. Having carefully studied numerous guidebooks before we went, I made a reservation (via a postcard I mailed from the US) at a restaurant that was billed as “typically Costa Rican on a working ranch in the hills of Escazu overlooking San Jose”. Since we were staying in Escazu it seemed ideal, and the guidebook description made it sound special. And our first full day in Costa Rica happened to be our wedding anniversary so I had an excuse to splurge, though I had no real concept of what the meal would cost.

When we arrived at our Aparthotel, there was a note saying we had a reservation at Tiquicia. I asked for directions and was told I should have no problem finding it. The woman drew me a map which essentially told me to turn right at the main road and then take the left fork a block ahead. After that the instructions were simply to keep going and follow the signs.

We drove for many miles and only saw one sign. And that sign indicated the restaurant was both straight ahead and to the right. We tried to the right, but when that road turned into what looked like an alley, we retreated and took the other road. Fundamentally, the way you find your way around in Costa Rica is to stop every quarter mile and ask somebody which way to Tiquicia (or wherever you are going). We did this and they kept pointing up hill.

The further uphill we got, the worse the road got. By now it was dark, the road had degenerated to a one lane (barely) rocky path that looked like it was only good for oxen. We were sort of in the woods and hadn’t seen anybody for a few miles. A right turn and the road was heading steeply downhill (up to this point we had climbed considerably), but we decided to brave it and headed down the most treacherous little path you would ever want to see. Suddenly, just ahead there was some sort of building and next to the building was a parking lot with some, believe it or not, tour buses in it. We were there!

But we didn’t really realize what “there” was until we were ushered to our table. The restaurant was situated on the edge of a cliff. We were given the prime table in a crowded restaurant. In front of us was a 180-degree panorama of the lights of San Jose and the neighboring parts of the central valley. The sight was truly breathtaking.

The owner came over to greet us and congratulated us on our wedding anniversary. He was surprised to hear that it was our first time at the restaurant since we had written ahead from the USA. The restaurant had no electricity; the meal was cooked with wood, and we ate by candlelight. We had a great array of Costa Rican specialties and after the meal we were treated to nearly an hour of folk song and dance on the patio a meter below our table. (They did have a battery or generator-powered floodlight for that event.)

We later learned that this folk dance occurs only on Friday evenings and fills the restaurant, mostly with tourists transported from San Jose hotels via tour buses. We took a different route down which was a bit shorter but no less treacherous. How the buses manage is beyond me. (By the way, dinner for two with salad and dessert set us back almost $20!)

Next Five days in Costa Rica

On our second day, February 29 — it was a leap year — we visited the Irazu Volcano.

Returning to Escazu from Irazu I took these photos.

We visited Santa Cruz on March 1, and of course we got rain.

We had lunch, or perhaps a late breakfast, in Paraiso and experienced more rain. A group of cyclists waited out the rain and others shared umbrellas.

In Heredia a young woman got some appraising looks.

And a young girl posed in a frilly outfit.

Another day and another rainbow.

On March 2 we travelled west to the coast and took a boat to Isla Tortugo.

It had a beautiful white sand beach.

A great spot for sunbathing and beach volleyball.

I found a Red Land Crab to photograph.

We had lunch on a deserted island and fruits were available on our trips both out and back.

The sun was setting when we returned.

On March 3 we travelled south to the Orosi River Valley and Tapantí National Park. I see Rancho Naturalista is on this map. We plan to visit it Day 3 of our 2025 trip.

.

You can see Jann carrying an Olympus OM-2S camera. Back then I was carrying two OM-4 cameras. Amazingly. I am currently using an OM-1. Those 1992 cameras were, of course, film, and mine is now digital. In the film days most camera companies designated newer and/or higher-end cameras with higher numbers, like my OM-4. These days the top-of-the-line digital cameras normally have a “1”, like the OM-1, and newer models are Mark II, Mark III, etc.

We visited Tapantí National Park, which is one of the wettest areas in Costa Rica, saw a nice waterfall, and took photos of the jungle and large, interesting leaves.

Continuing our apparent fascination with volcanos, on March 4 we visited Poas Volcano north of San Jose (see previous map).

I took a few photos while driving down from Poas.

I was intrigued by the bananas.

Before retuning to San Jose, we visited La Paz Waterfall Gardens Nature Park and the tallest waterfall in the country — with a 90-meter drop — Bajos del Toro Waterfall.

We discovered an interesting use for egg shells,

photographed a pattern of interesting trees,

and enjoyed the setting sun.

Manuel Antonio National Park

After six days in the San Jose area, we headed West over the mountains by the “back road”. This was claimed to be the shortest route to Quepos and Manuel Antonio National Park, both in terms of distance and time. But boy it sure was a rough road. It must have been about 100 kilometers (60 miles), and it took us a good three hours. But suddenly you see the coast and descend quickly to the town of Parrita.

From there to Quepos, you drive miles of flat, wide rock and sand roads with a one lane bridge over a small river every quarter of a mile. On both sides of the road lie African Oil Palm plantations – miles of palm frees evenly spaced in two dimensions. The fruit is golf ball sized red and black berries in bunches larger than a large watermelon.

Beyond the palms to your right about a mile is the Pacific. To your left ten miles are mountains, beyond them the mile high Central Valley and then, within a hundred miles, the continental divide. Though dry and sandy, the land has a lushness to it. You pass a smoking palm oil factory and roll down your windows to sniff the strange smelling, slightly sweet smoke.

We stayed two nights in Quepos and headed out very early each morning.

The town of Quepos has a few dirt streets and little stores and markets, but five miles beyond lies Manuel Antonio National Park.

Manual Antonio is a small park with its entrance protected by an estuary. To enter you must wade across the estuary through water ankle deep at low tide or waist deep at high tide. (Stay six hours and you get one of each.) Like most of the parks in Costa Rica, it has my kind of hours Manual Antonio opens at 7:00 am, though there is no gate and arriving early simply means you save the 100 colons entrance fee.

Combine a very generous amount of the finest sand from Cape Cod National Seashore with the warm water and perfectly shaped waves of Hawaii and add a lush South American rain forest. Toss in rocky headwalls from Mount Desert Island every so often to form a series of distinct beaches cut off from each other and varying in length from a quarter mile to over a mile. The jungle provides shade for the sunbathers; it lies 20 to 100 feet from the water’s edge. And the jungle-covered headwalls (cliffs) provide spectacular views of the beaches and the forested islands just offshore that provide nests and shelters for brown boobies and pelicans among other birds.

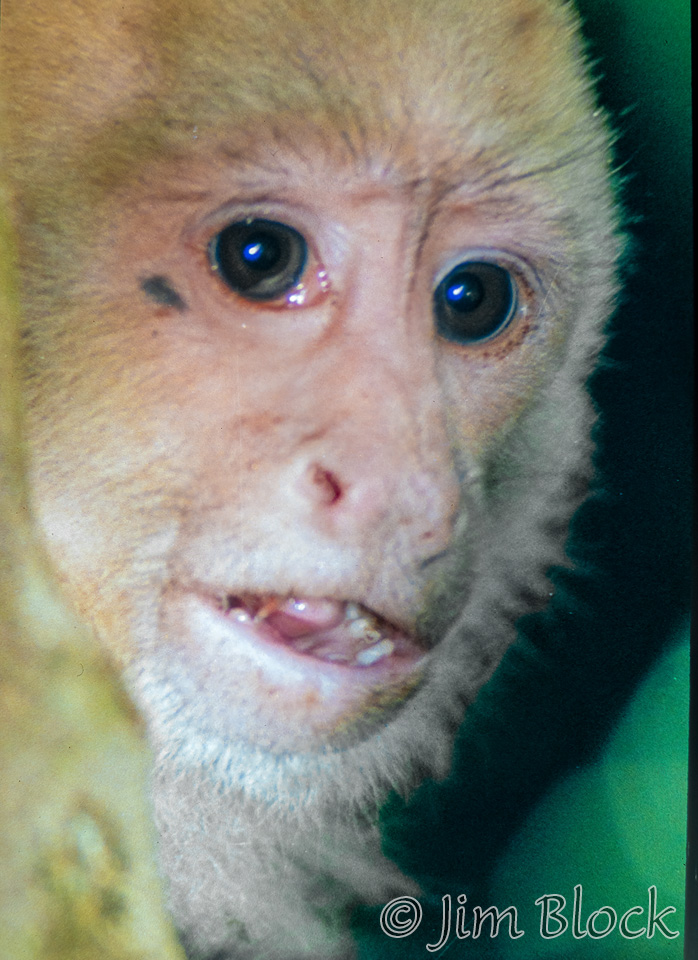

Ten to twenty feet inside the jungle is a sandy path lined with strange plants, wild flowers (and more hibiscus than you have ever seen), white-faced monkeys, sloths, agoutis, peccaries, coatimundis, and iguanas. If you walk around for more than an hour and are reasonably observant, you see them all, as well as some of the over 350 species of birds reported in the park. You tire of watching several families of monkeys play in the trees a few feet away, walk ten feet to the sand, another 30 feet to the water, and you are snorkeling amid colorful tropical fish, but no coral to speak of. (It was reportedly killed years ago when the water got too warm.)

Monkeys and Beach

Panamanian white-faced capuchin monkeys were everywhere along the path. Here is a collection of photos.

Just a short distance from the path with the monkeys was a series of beautiful beaches.

The second day we ran into a paddle tennis partner opponent from Hanover travelling with a bird and nature tour group. She looked great with a trim figure and with her short blond hair not quite reaching her bare, tanned shoulders. We both hope we are in as good a shape when we reach seventy something.

Sloth Up Close

Six am, temperature in the mid to upper 70s. I’m wandering the grounds of our small “hotel”; photographing exotic orchids while waiting for Jann. I strike up a conversation with a couple. The woman asks me if I am waiting for a guide. When I say no, she indicates they are. They have been into Manuel Antonio Park numerous times over the last several days but think they will see more animals if they go with a guide. They haven’t yet seen a sloth. We did, on a boat trip several days previous, but the sloth was high in a tree asleep and looking up at the blob it was impossible to tell which end was up or distinguish much of anything in the mass of fur. I wish them good luck as Jann joins me and we hop in the car for the short drive to the park.

It is early and we are able to get a prime parking spot under a tree right along the beach. We walk down the beach; gee, there are a lot of people wandering around this beach and it’s not quite 7:00 am.

Before wading across the estuary that guards the entrance to the park, we decide to warm up our cameras with a few quick shots of the overall scene. Doing this I catch sight of three people walking down the beach toward us. One guy was carrying a branch with what looks like a stuffed monkey attached. What a stupid prop for tourist photos!

As they get closer, I recognize the couple I had spoken with minutes before. The third person is their guide, and the monkey is neither stuffed nor a monkey. Seems the guide found a sloth in town and was bringing him back to the park where presumably it would have a better shot at finding a mate.

For those who care this was a three-toed sloth (as distinguished from the two-toed variety). It must have weighed 20-30 lbs. and if stretched full length was probably about 4 feet, most of that length being arms and legs. He (or she, I couldn’t tell) clung to the branch at various times with two, three, or four appendages. Occasionally it worked its way along the branch, but true to its name it was pretty slow moving. Its furry face was a cross between a raccoon and a teddy bear, and it looked sad. But it must have trusted the guide since it never once attempted to escape or even let go of the branch. Or, more likely “run away” is just not something a sloth does.

Well, the sloth ploy worked because it didn’t take long for the guide to convince Jann that we ought to cough up $20 each and join their “tour”. Several interesting birds and animals later we stopped at a picnic table just inside the shade of the forest along “Third Beach”. Out of the guide’s backpack came a breakfast of cheese bread and fresh fruit. The branch and sloth sat quietly on the sand beside us. (Neither moved much.) Nosy tourists (notice how I detest tourists) came over to see the sloth. One man who attempted to pet it almost got clawed as the sloth took a relatively swift swing at him with its long arm. The guide carried that sloth a long distance (the guide was fairly muscular and needed to be) before finding exactly the right tree for it. Sloths eat leaves in only particular trees and once a week come down from the tree to defecate. They are cute animals and most tourists in Costa Rica do not feel fulfilled until they have seen one (we saw about six different ones in our travels).

When the two-hour tour was over, we headed for a rocky little cove we had seen the previous day and went snorkeling. After further wanderings along the beaches, we returned to our room, showered, packed up, and checked out well before 11:00 am.

Leaving Manuel Antonio we travelled about 30 miles along a bumpy dirt road, but one that was in relatively good shape, before we found pavement and our pace quickened. We would be travelling northwest along the Pacific for a while before heading inland toward the mountains and Monteverde.

Up To Monteverde

Around lunch time we saw a sign “Playa” (beach) and turned left on a winding dirt road. In about half a mile we found a “cowboy” near his horse mending barbed wire fence confining steer with the strangest hump on their backs you would ever care to see. They were both ugly and beautiful (with long lop ears) at the same time. A half mile later the road terminated at the beach with beautiful fine sand and crashing surf as far as the eye can see in both directions. Absolutely nobody was within view.

Further along, the road turned inland and ended at the Interamerican Highway. On this beautiful sunny afternoon, with no traffic, we were within a few miles of our turnoff to Monteverde when some strange looking guy in a uniform in the road ahead waved me to pull over. I slowed down trying to figure out if he was a renegade commando or what and then I saw his buddy hidden in the woods with a hand-held radar gun. Seems I was going 88 in a 75 zone. But hold it folks, those numbers are kilometers per hour. In terms you are more familiar with, the speed limit was about 46 mph, and I was only exceeding it by about 8 mph.

The cop looked at my driver’s license, my passport, my auto rental agreement, and then proceeded to flip through my passport over and over again. I thought briefly about asking if he wanted to see my birth certificate too, but his English wasn’t great and my Spanish was nonexistent, so I feared he might not see the humor in my offer. He told me that the fine was 2,000 colons and that I had to pay it tomorrow in San Somethingorother. I groped for a map and realized this place was 50 miles backwards, and we were heading up into the mountains on what I knew to be a very rough road. We had reservations and plans, and I had no intention of spending tomorrow retracing my steps just to pay a ticket. I told him that, in a very nice way, and he repeated that I had to be there tomorrow while flipping incessantly through my passport. I never did get around to asking what would happen if I didn’t show up (I thought better of that question), but the guidebook did warn of people being “detained” at the airport for unpaid tickets.

After conferring with his buddy, more flipping through my passport — I think he was stalling hoping an inspiration would strike him or I would boldly offer a solution — and more nice but firm “it will be very difficult for me to be in that town tomorrow” protests from me, he finally suggested that I give him the 2,000 colons and he will personally pay my fine for me tomorrow. I gladly handed him the money, grabbed my passport, and left without any documents changing hands. As this was happening, Jann was mumbling something in my ear about getting a receipt, but something told me that it might not be the right request to make given all the circumstances. To this day, I am not absolutely sure that he and his buddy split the 2,000 colons. By the way, 2,000 colons was a bit less than $15.00.

From the turnoff it was 33 kilometers (about 20 miles) to our destination, Monteverde. It took us about two more hours to get there. Less than half of that time was spent photographing the countryside; the road was quite rugged as it wound up into the mountains. But it looked like it hadn’t rained in years so at least we didn’t have mud to deal with.

Our hotel in Monteverde was very, very enjoyable. It was a relatively small three story wooden Swiss chalet owned and run by a couple from Chile. As we were nearing the end of the dirt road, I remarked that what I really wanted for dinner was something typically Costa Rican like rice and beans and beef. Guess what the hotel served for dinner that night (everybody had the same meal)? Goulash (beef) with rice and beans. The meal was delicious and the view from the balcony overlooked the Gulf of Nicoya and the Pacific Ocean and of course the setting sun.

Before dinner I hiked below the hotel and managed to get a photo of yet another rainbow.

We plopped into bed around 8:00 pm that night to do a little light reading. Minutes later the whole room starting shaking. It built in intensity, died down, and then resumed with increased intensity. No damage was done but the place really shook — I mean shook! It felt like it lasted 30 seconds, but it probably only lasted 15. The next day we learned that we were 25 miles from the epicenter of a 5.8 earthquake. (Various other sources put the earthquake between 5.7 and 6.0.) The only impact that I could tell was a lukewarm shower in the morning because one of the pipes in the hotel broke.

Monteverde Cloud Forest

Monteverde is a very pleasant small town in the mountains, but the real attraction is the Monteverde Cloud Forest. It lies on the Continental Divide in north central Costa Rica. In 1949, four Quakers were thrown in jail in Alabama for refusing to register for the draft. After their release, they searched Canada, Mexico, and Central America for a place to settle where they could live peacefully. They chose the Monteverde area because of its pleasant climate, its fertile land, and because it was far enough away from San Jose to be relatively cheap to buy. Seven families arrived in 1951, some making the overland journey by truck which took three months (I suspect the last 33 kilometers took at least half of the time.) They began dairy farming and cheese production, and currently Monteverde cheese is sold throughout Costa Rica.

When the Quaker settlers first arrived, they decided to preserve about a third of their property in order to protect the watershed above Monteverde. In the 1970s and 80s, with the help of several national and world wildlife and conservation organizations, the reserve expanded and is currently operated by the Monteverde Conservation League, a private group. In 1988, the MCL launched the International Children’s Rain Forest Project whereby children in school groups from all over the world raise money to buy and save tropical rain forests adjacent to the preserve. Children can also come for educational programs. This totals over 20,000 acres and continues to be a private operation. It appears to me to be one of the most popular tourists’ destinations in all of Costa Rica, at least for nature lovers. Yet it remains very isolated (the road in truly is terrible), untouristy (there are essentially no restaurants, just some low-key hotels), and very nature oriented. They only allow a hundred people into the preserve at a time, so unless you arrive early in the morning (as we did), you might have to wait outside the entrance in the mist for quite a while. As we left, they took careful note of our departure and admitted two people from the group standing around the entrance.

The morning of our visit to Monteverde Cloud Forest began with a huge breakfast at 6:00 am. We then went to the hotel’s boot room to try on boots. It was quite a struggle not only to find some that fit reasonably well but also matching pairs. But eventually we succeeded and headed three miles up the road to the entrance to Monteverde. We felt somewhat silly and somewhat skeptical wearing boots that came almost to our knees when it clearly hadn’t rained in this area in years. But we had previously experienced some of Costa Rica’s microclimates and had both read the guidebook and talked with others at our hotel who had visited the day before, so we were expecting that the boots probably would come in handy. I asked how I would do in Teva’s. The answer was, no way.

A mile from the entrance it was dry and sunny, but as we entered the parking lot it became a bit misty. Fifty feet away was the entrance to the forest and once inside the forest it was soaking wet. Out came our ponchos to ward away the rain and off we trudged, sometimes through mud over a foot deep.

Seven miles later, some of which were along the continental divide, we emerged from the forest cold and wet and pretty much covered with mud. The boots helped a lot, but the mud managed to find its way onto pretty much every piece of clothing we had on. And by then the electronics in both of my cameras were kaput.

A mile down the road it was hot and sunny, and after about an hour under the hair dryer at our hotel room, my two cameras were as good as new. The rain forest at Monteverde isn’t much different than many of the other rain forests/national parks throughout Costa Rica. It’s wet and you see a tremendous variety of trees, epiphytes (air plants growing on frees) and flowers – and some birds although you see more of them outside the forest along the road. However, the whole experience of Monteverde, the village, the hotels, the ambiance, the people is very special.

That afternoon we visited a butterfly garden.

The grounds of the hotel had feeders to attract hummingbirds. Amazingly I managed to get one decent photo of a Purple-throated Mountain-Gem.

Next Four Days

Bebedero River cruise

After leaving Monteverde, we managed to find our way to the Bebedero River where we took a boat ride.

From the boat we were able to photograph a number of species.

Tilaran Area

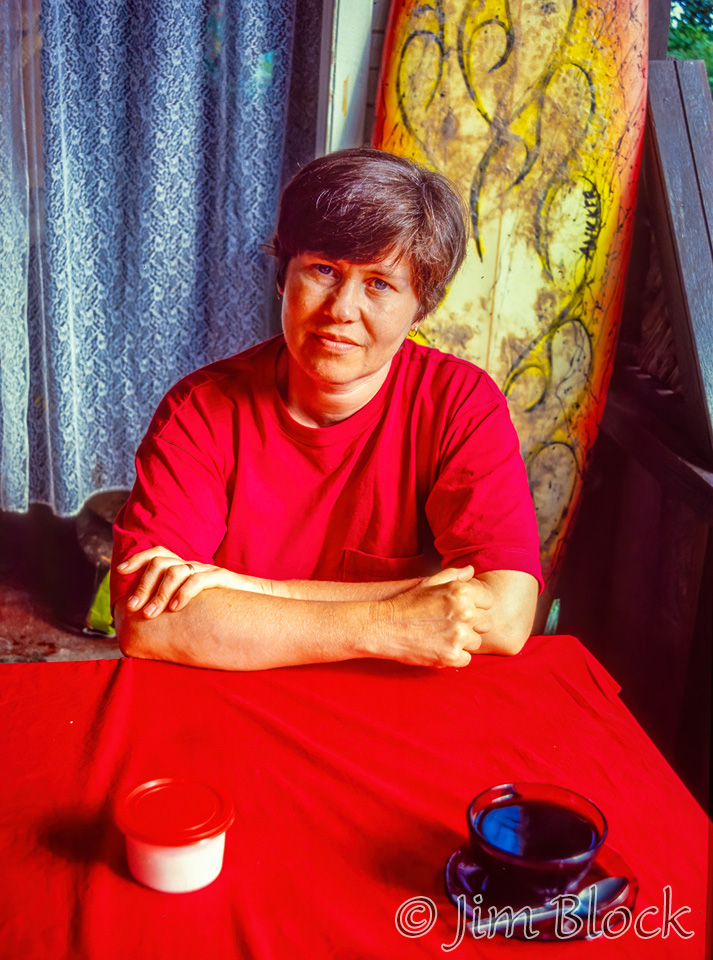

We had lunch in Tilaran at a small cafe.

We spent the rest of the day exploring the area and photographing children.

Liberia and Playa Hermosa

The next day we visited Liberia on the northwest coast.

We found our way to Playa Hermosa.

On and near the beach we photographed more interesting species.

We headed back to the Lake Arenal area for the night.

I liked the dramatic late afternoon light on this scene.

We watched the sun setting over Lake Arenal.

Fortuna

On March 10, we drove from the Arenal area to Fortuna then on to Selva Verde Eco-Lodge to spend the night and the next day.

In Fortuna I photographed these young woman and noted one must be careful not to park to close to the “curb”.

And I enjoyed photographing children with umbrellas.

Then an interesting flower that I have not identified.

I liked the repetitive pattern of these trees.

We arrived at out lodge at Selva Verde late in the afternoon.

I’m not sure if the photo below was evening or morning.

All night long I listened to the rain and feared our next day would be a washout. But in the morning I realized I was just hearing the Sarapiquí River.

We toured the reserve. I took a distant photo of a Flame-rumped Tanager.

And then some plants I have not identified.

It appears that an insect was feasting on this leaf before it unfurled.

A Golden Silk Spider “posed” for me.

These beetles seem to be mating.

On a wall of a structure slept Proboscis Bats.

Los Canales and Tortuguero

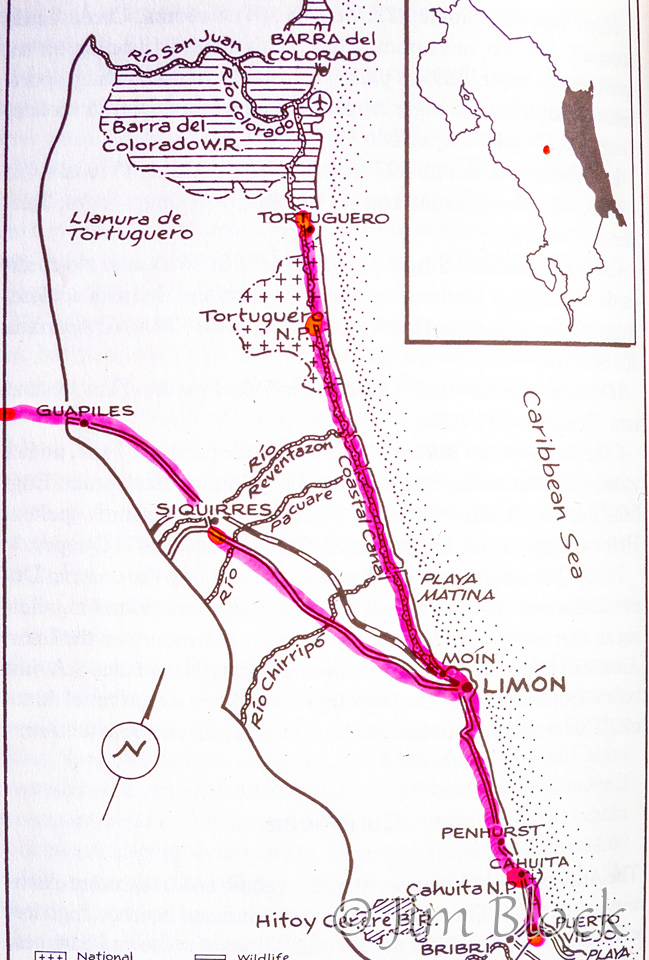

The next day we headed to Limon to take a boat along the Coastal Canal to Tortuguero. We would then headed south to Cahuita and Porto Vejeio.

And we are off.

The Caribbean coast has only one major city, Puerto Limon, which was visited by Columbus in 1502. On April 22, 1991, a 7.4 earthquake hit this area killing 50 people in Costa Rica and 30 in Panama. The epicenter was just south of Limon. We saw numerous destroyed buildings and bridges down, and the traffic on the canals (see below) is just now getting back to normal. About a third of the people in Limon are Blacks, and they speak a delightful brand of English as they are mostly of Jamaican descent. Limon reminded me of parts of Belize.

There are no roads north of Limon up the Caribbean coast. Transportation is by boat (or small plane if you are a wealthy tourist or a fisherman in a hurry). As the mountain rivers reach the Caribbean they slow down and deposit their sand in great wide deltas. Over the years these deltas nearly merged, producing a new coastline and a 60-mile-long sand bar perhaps a mile wide. The sand bar became jungle covered and was separated from the mainland by essentially one long river which paralleled the coast. By digging a few strategically placed canals, the system became a tremendous inland waterway carrying villages, lumber, fruits, fishermen, and tourists.

The earthquake raised parts of this system four feet and hence significantly disrupted boat traffic for almost a year. Tourists from Limon had to be bused inland and then brought down one of the rivers to connect with the canal system. We took a very delightful boat trip from Limon 70 km along the canal to Tortuguero, seeing some of the shifted land and a barge dredging part of the canal. Our boat dragged along the sandy bottom for a while here, but we managed to make it through this one remaining trouble spot. Tortuguero is a picturesque but small village with a few rustic lodges and probably only a few hundred permanent residents.

Some people lived along the canal on a narrow strip of sand bar separating the river from the Caribbean.

High in a tree a spider monkey was backlit against a blank sky.

And we found our second Three-toed Sloth.

And a Spectacled Caiman.

Here are some of the birds we saw, with their species under the photos.

This photo has long been a favorite of mine. Perhaps the soft light and the colors please me.

We finally got to something like a beach. No turtles this time of year.

In addition to the natural beauty and the excellent fishing in the rivers and the Caribbean, Tortuguero is famous as the nesting site for the green turtle. Thousands of these turtles mate in July and August. But the female does not return to lay her fertilized eggs for 13 months. Each one then lays about 100 eggs over a period of weeks covering them with sand for protection. After an incubation period of two months, the hatchlings scramble out of the nest and head for the sea in a perfectly straight line, A year later the few percent that survive weigh about a pound and at full size they can weigh over 400 lbs. Since it was neither night nor the right season, we did not see the turtles, but we did see the beach. It stretched “forever” in both directions.

Here are some of the other people and scenes along the Coastal Canal.

Limon, Cahuita, and Porto Vejeio

We spent the afternoon of March 13 in Limon. My memory of that area is fuzzy. I photographed a young girl.

There are bananas are under the blue bags.

We stopped along the coast to see the sights and stayed the night in a nice lodge.

It looks like we had an elegant dinner.

The next morning after breakfast, we took photos as we headed south to Cahuita.

I believe we had lunch in Cahuita before visiting the Cahuita National Park.

In the park we saw crabs and periwinkles.

I liked the way the Small Periwinkles marched in a row.

We also saw a Brown Basilisk lizard.

And we photographed a Golden Silk Spider from both sides.

We found a partially-black sand beach in Porto Vejeio.

Not wanting to visit Panama, we headed back through Cahuita to Limon where perhaps we spent a second night.

Braulio Carrillo National Park

On our last day in Costa Rica we visited Braulio Carrillo National Park enroute back to San Jose. Note again that our ponchos came in handy.

Back to Escazu and then home

We returned to Escazu and then the airport in San Jose the next morning. Along the way we saw the Sucio River. The river gets its name from the sulfur deposits found on the Irazú Volcano, which give the waters the yellow color. The Sucio River begins half a kilometer from the top of the Irazú Volcano.

There was some scenery enroute.

I very much enjoy photographing people, and I was able to do some of that in Escazu before our flight home. Note the Harvard sweatshirt and the reflection in the motorcycle mirror.

I close with two churches in Escazu.

Closure

(I have slightly modified the closure to reflect places and sights I covered on this page but not in the original “trip report”.)

In this overly long article (I got carried away!), I have described a small portion of our trip. We took three spectacular boat trips along waterways lined with birds, monkeys, and crocodiles. We cruised in the Gulf of Nicoya and had a gourmet lunch on a deserted island. We saw a formerly small lake which drained into the Atlantic before it was turned into a large lake (Lake Arenal) that now drains into the Pacific and has some of the best windsurfing (consistently high winds) in the world. We heard a volcano rumbling and after some rain delays finally make it up to Poas and peer into the mile wide crater and the the bubbling lake at its bottom. If you ever think of visiting a Caribbean Island, consider Costa Rica instead. It is a wonderful country with friendly people.